NATIONAL ATR NETWORK SURVEY

Hundreds of ACEs, trauma, & resilience networks across the country responded to our survey. See what they shared about network characteristics, goals, and technical assistance needs.

Trauma-Informed Efforts at One Alaska Elementary School

Before Deanna Beck had ever heard of the 1998 ACE study, before she became principal of Northwood ABC Elementary School in Anchorage, she was a special education teacher who saw the ways trauma scrawled through her students’ lives.

On the one-minute reading tests Beck administered, she would notice steady progress—40 words a minute, then 50—followed by dramatic drops; a child would suddenly be stumbling along at three or four words a minute.

She began to ask the kids what had happened. “My mom’s boyfriend was over last night…We had to go to the shelter…I didn’t get any sleep.” Beck started asking more questions in an effort to know her students better.

She began to ask the kids what had happened. “My mom’s boyfriend was over last night…We had to go to the shelter…I didn’t get any sleep.” Beck started asking more questions in an effort to know her students better.

“When I moved to being a school principal, I saw this on a larger level—one or two kids in each classroom who were just blowing out. [I wondered]: Were they fed? Did they have a place to sleep? Do they feel safe? I realized that there was so much going on outside of school that was coming into school. I realized I had to partner with parents, and also help teachers understand.”

Beck was Googling “things that happen to kids” in 2013 when she came across the ACE study. The statistics confirmed what she’d been seeing; the study also gave her cause for hope and a spur to action.

I thought: This is what we can do as a school. We can give these kids this one caring adult.

She was struck by research on protective factors that showed one of the most important buffers a child can have is the presence of one unconditionally caring adult. “I thought: This is what we can do as a school, We can give these kids this one caring adult.” So Beck launched a three-year plan to make Northwood Elementary a compassionate constant in kids’ lives.

She knew teachers had to come first: if they were stressed and burdened, they wouldn’t be able to attend fully to their students. So the first year of her rollout focused on staff education and wellness. Teachers read and discussed Fostering Resilient Learners: Strategies for Creating a Trauma-Sensitive Classroom. She used Title I funds to bring staff in for extra professional development. Beck encouraged them to take the ACE survey and reflect on their childhood histories; she was open about her own.

“I share that my ACE score is 2. I have teachers who have ACE scores of 9. They say, ‘This happened to me, and I want to be there for our students.’”

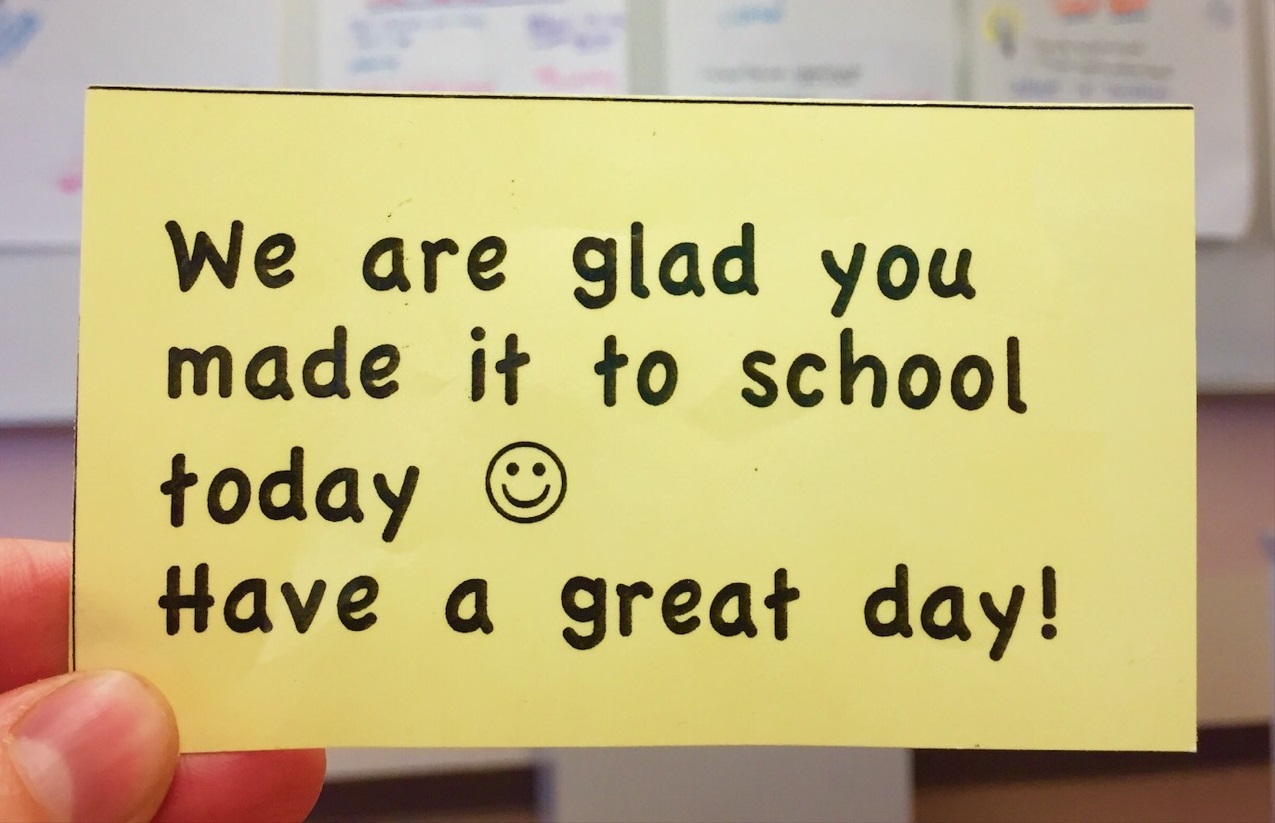

Word of the changes at Northwood reached Laura Norton-Cruz, director of the Alaska Resilience Initiative (ARI); on a visit to the school, she was struck by the welcoming climate. A staff member stationed at the door greeted every child by name; “tardy slips” had been recast to read, “We are glad you made it to school today. Have a great day!” Instead of after-school detentions, students who acted out were given “time in”—that is, one-on-one time with a teacher to talk about what motivated the problem behavior and what they could do to repair any harm.

Word of the changes at Northwood reached Laura Norton-Cruz, director of the Alaska Resilience Initiative (ARI); on a visit to the school, she was struck by the welcoming climate. A staff member stationed at the door greeted every child by name; “tardy slips” had been recast to read, “We are glad you made it to school today. Have a great day!” Instead of after-school detentions, students who acted out were given “time in”—that is, one-on-one time with a teacher to talk about what motivated the problem behavior and what they could do to repair any harm.

ARI is a connecter and convener; part of its mission is to link people and organizations that have been doing trauma-informed work for years. Norton-Cruz snapped a photo of Northwood’s “glad you’re here” slip and posted it on ARI’s blog.

“The immediate thing I needed to do was take pictures and post their story on social media,” Norton-Cruz says. “Something good is happening; people need to know about it. People need to be inspired by this example of how to apply the [trauma-informed] lens.”

Beck asked Norton-Cruz to speak at a fall showing of Resilience for Northwood parents; in turn, Norton-Cruz invited Beck to join the ARI’s trauma-informed systems change work group. And when Norton-Cruz spoke to a gathering of Anchorage’s 63 elementary school principals in early August, introducing ACE science and the concept of trauma-informed schools, she pointed to Beck’s work.

“I tried to share her as an example. Since then, a lot of principals have reached out to her,” Norton-Cruz says.

Those principals often want a blueprint for how to make trauma-informed change in their own schools. “I tell them there’s not a set curriculum,” says Beck, now in her sixth year as principal. “You have to figure out what works for your school, for your community.”

She’s eager to share what has worked at Northwood. The second-year focus was on school policies and students’ experience; an “adopt-a-student” program encouraged staff to reach out regularly to the students who seemed most isolated. After just one year of that concerted effort, surveys showed a 29% increase in the number of students reporting they had five or more adults at school whom they could rely on.

This year, the school is emphasizing parent and community engagement. Beck scheduled a second showing of Resilience; during a fall professional development day, teachers visited homes of selected students—not to discuss academic or social problems, but simply to build relationships with families.

Meantime, as a member of the ARI work group, Beck feels linked to others who are doing similar work, not only in Anchorage but across the state. She helped the ARI create a videotaped presentation about ACEs and trauma-informed schools that was shown in November at a training for the district’s elementary staff; each principal has formed a leadership team to map out next steps for that school.

“It makes me really happy that I’m not alone, that I’m not the only person who sees this,” Beck says. “There are people I can tap for help. We can affect a greater community.”

This article is part of a community update series following the ATR networks participating in the MARC 1.0 Initiative. Read the other updates from Alaska:

This article is also part of the Community Voices series.